1972 riots: Was it a language issue?

| Author | Sibte Hasan |

|---|---|

| ڪيٽيگري | Language & Politics |

| ڇپيو/ پيش ٿيو | 23/09/2015 |

| ڇپائيندڙ | http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153263 |

| اپلوڊ ٿيو | 02/03/2023 |

| ڊائونلوڊ | 260 |

| قيمت | 0 |

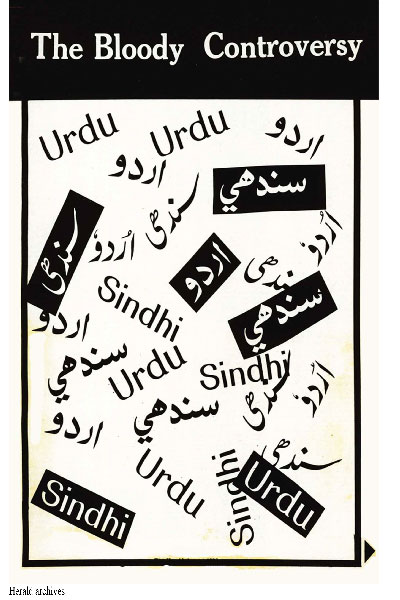

Now that peace has been restored and

sanity is returning to the frenzied people, it is time to coolly ponder over

the main causes of mutual hatred and suspicion between the Sindhi and Urdu

speaking groups in Sind.

It would be naïve to think that the

amicable settlement of the language issue will be itself remove all the

barriers that have been raised by the interested parties between the old and

new Sindhi population. The controversy over the Language Bill is the symptom of

a deeper malady and part of a large socio-economic conflict which has arisen on

account of the new ethnological pattern of Sind. Unless serious efforts are

made to resolve this basic conflict it might endanger the unity and solidarity

of the entire country.

Let us examine its cause in their

historical perspective:

Prior to partition, the population

of Sind happened to be a composite ethnical unit. An overwhelming majority of

the people were Muslims. Their main occupation was agriculture. Most of the

land was owned by big landlords, pirs and waderas and cultivated by the haris

whose life of privation and misery is too well known to be described here.

Literacy among the Muslims was negligible and there was a very small educated

Muslim middle class consisting of traders and lawyers. They were mostly

concentrated in Karachi.

The urban economy was controlled by

the Hindus, although they formed a very tiny minority in the province. They

were money lenders, traders and businessmen. Whatever industries there were

also belonged to the Hindus. Most of the medical practitioners, engineers,

college teachers and lawyers too were Hindus. They dominated the political and

cultural life in the major cities.

When the Hindus left the country

after partition, the vacuum was filled by the Muslim refugees from U.P., C.P.,

Bihar, Rajisthan, Kathiawar and Gujrat. Karachi became the capital of Pakistan

and its population soon swelled from three lacs to more than a

million-and-a-half. Most of the buildings belonging to the Government of Sind

were acquired to accommodate the offices of the Central Government and its

staff which mostly came from the Punjab, C.P. and U.P.

If any evidence was required to

prove that the language controversy is essentially a socio-economic phenomenon,

it was provided by the agitators themselves. While the early slogans were quite

innocuous “Urdu Sindhi Saath Saath”—the mood changed as the agitation gained

momentum. Soon the formality of tying Urdu with Sindhi was discarded and the

call was confined to “Urdu only”.

The local Sindhis residing mostly

down-town in the metropolis warmly welcomed the mohajirs and assisted them in

occupying the houses and shops evacuated by the Hindus. The same thing happened

in other major towns of Sind, with the result that today the new Sindhis form a

majority in Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Mirpurkhas, Khairpur, Nawabshah and

Tando Adam. In Larkana they constitute about half the population. The old

Sindhis are in a majority only in Thatta, Sanghar, Dadu and Jacobabad.

The refugees were allotted most of

the evacuee property — land, houses, shops, factories, etc. They also occupied

most of the vacant and newly created posts in the Administration. Thus the

influx of millions of refugees from across the border introduced a new ethnical

element in the body politics of Sind. Their mode of life and cultural

traditions, their language and literature were substantially different from

those of the local people although they all professed the same religion.

But these refugees were not a

monolithic body. Among them were shrewd businessmen, industrialists and traders

from Bombay, Agra, Sawnpur, Ferozabad, etc. They possessed capital or know how

to acquire it. They had talent and business experience. So they were allotted

factories in Hyderabad, Sukkur, Kotri and Khairpur — oil mills, tanning

factories, rice housing mills, biscuit factories, etc. Their capital increased

and today out of ten textile mills in Hyderabad nine belong to non-Sindhis.

Similarly, tanneries belong to the Cawnpore group. Glass bangle factories are

owned by the Ferozabad group and the shoe-making industry is controlled by the

Agra group.

The commercial and industrial growth

of Karachi need not be discussed in detail. We know that all banks, insurance

companies and the vast manufacturing complex at SITE and Landhi-Korangi belongs

to new Sindhis capitalists who came either from Gujrat and Bombay or from the

Punjab. The Urdu speaking population of Karachi is mostly employed in offices,

factories and workshops or is engaged in petty trades. Some of them are also serving

as lawyers, doctors, teachers and engineers. Quite a large number still dwell

in jugis and are yet to be properly rehabilitated.

Most of the Urdu speaking

inhabitants of other major towns in Sind also professionally belong to the same

categories.

LAND

About 40% of the agricultural land

was declared evacuee property in Sind and as such was allotted to the refugee

landlords who mostly live in Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, etc. and visit their

estates only to realize the rent. Moreover, most of the barrage lands (Sukkur,

Kotri and Guddu) were generously distributed among the retired Army and

civilian officers belonging to the Punjab, Sarhad and Karachi. The local haris

did not get any share in these valuable lands in spite of solemn pledges by the

other fertile lands were allotted on very cheap terms to Gujrati and Punjabi

industrialists for large scale farming. These farms are now serving as a very

good cover for evading income tax on industrial products.

SERVICES

AND EMPLOYMENT

Prior to partition the ratio of the

Muslim staff in services in Sind — both Government and private — was not more

than 5%. The number of Muslim gazetted officers could be counted on one’s

fingers! Most of the top officers in every department were Hindus and when they

left their vacancies were filled by non-Sindhi Muslims.

Before One Unit was formed in 1956,

there used to be a Provincial Assembly and a Provincial Cabinet in Sind. But

both were dominted by Sindhi waderas who, like landlords everywhere, pledged

their loyalty to the ruling class in their own selfish interests. They never

stood for the right of the common man. Moreover, they were always at the mercy

of the autocratic Central Government and the bureaucracy. When One Unit was

formed, even this façade of provincial autonomy was removed. Sind was governed

from Lahore and when Ayub Khan Shifted the capital to Islamabad the Vicious

circle was complete.

But the situation in Sind did not

remain static. A new university was established in Hyderabad in 1951-52. New

colleges and schools were opened in various other towns and soon an educated

middle class of old Sindhis started emerging. This class wanted employment and

its legitimate share in the services. But there was no machinery to provide

them with these facilities. Resentment among the educated unemployed grew.

Meanwhile, a section of small

Sindhi-traders was also aspiring to rub shoulders with the Gujarati and Punjabi

big business. It too wante dits share in lincences, permits and allotments so

generously showered on others in the past. But to their gangrin they found that

they had arrived on the scene too late! They could not compete with the big

sharks.

Thus the resentment felt by the

indigenous population of Sind, especially waderas, traders and middle class

intelligentsia against the new Sindhis can be traced to the following economic

realities:

1.

Allotment

of evacuee property — land, factories, shops, houses, etc. to the refugees;

2.

Allotment

of barrage lands to the retired civilian and non-civilian officers, not

belonging to Sindhi;

3.

Grand

of licences, permits and other facilities to new Sindhis to install new

industries and commercial concerns;

4.

Emergence

of an educated Sindhi middle class which found all avenues to services closed

to it;

5.

The

establishment of non-democratic and unrepresentative governments both at Centre

and in the Province. The Governments never tried to solve any of the problems

facing the Sindhi people.

Herald archives

Some of the grievances, especially

against the Urdu speaking middle class were imaginary, therefore unreasonable.

For instance, if the Urdu speaking intelligentsia occupied most of the posts in

the universities and colleges in Sind, it was because they were the only

qualified people available. Similarly, if the Urdu speaking artisans and

technicians were more skilful in their profession than the local people, it was

not their fault. Or, if the Urdu newspapers, magazines and films or radio

programmes were more popular than their Sindhi counterparts, it was because the

standard of production of the former was higher than that of the latter.

In short, the Urdu speaking new

comers were not in the least responsible for the socio-economic backwardness of

the indigenous population. The causes for this backwardness are to be sought in

most oppressive and decadent feudal system which has been in operation in Sind

for centuries.

The general resentment against the

authorities as well as the new Sindhis was organized by Mr. G. M. Syed and his

supporters. The professed object of the ‘Jeay Sind’ movement was the (i)

abolition of One Unit; (ii) Complete Provincial Autonomy for Sind; and (iii)

the protection and development of the Sindhi language and culture.

The economic and political

implications of this programme were not lost to the new Sindhi landlords,

businessmen and their political henchmen. They had derived all their privileges

and benefits during the Ayub regime which they staunchly supported. Therefore

they did not want any change in the status quo.

It was to preserve this status quo

that the Mohajir-Punjabi-Pathan United Front was formed. This front was

patronized by the rightst elements lead by the Jamaat-i-Islami. It received

full monetary assistance from the businessmen of Hyderabad and Karachi and was

encouraged by the Urdu Press in the cities.

But neither of these two conflicting

groups was strong enough to fight its battle for economic supremacy without the

active cooperation of the lower middle class and the common man. Both of them,

therefore, used every means, fair and foul, to mobilize the people under their

banner and exploited their ethnical differences and cultural and linguistic

sentiments.

The haris and the educated middle

class among the old Sindhis, were told that the new Sindhis, specially the Urdu

speaking ones, were responsible for all their miseries. They were the usurpers

who had deprived the local people of all the fertile lands, lucrative posts and

economic opportunities. If the old Sindhis did not rise against the domination

of the new Sindhis, their ancient culture and language too will soon be wiped

out. The new Sindhis were told that they were the real founders of Pakistan and

custodians of its ideology. If they did not wake up in time the old Sindhis

would destroy their Islamic culture and their language (Urdu) which was the

national language of Pakistan and the symbol of its nationhood.

It is on record that the

bureaucracy, both Sindhi and non-Sindhi encouraged this controversy, sometimes

supporting one ethnical group and sometimes the other.

Slogans were written on the walls

and roads eulogising the “meritorious services of Ayub Khan.” And this happened

of all places in Karachi which had defeated the tyrant, in 1965 election in

spite of his threats to throw the Mohajirs into the Arabian Sea.

However, the country-wide agitation

against the military dictatorship of President Ayub Khan pushed the

Sindhi-non-Sindhi conflict, and the emergence of the People’s Party of Pakistan

as the biggest political force in Sind upset at least for the time being, the

nefarious game played by the reactionary elements.

In spite of the financial assistance

of the business community and full support of Karachi’s entire Press, both Urdu

and English, the Rightists were defeated at the polls in December 1970 but not

routed. Nor was their ideology demolished. As a matter of fact they have

regained their lost ground and regrouped their forces during the last one

year-and-a-half, thanks to the mistake committed by the PPP leadership.

The dependence on bureaucracy to

implement the People’s Government reforms, the failure of its labour and

agrarian policies, the appeasement of big business, the domination of waderas

over party machinery in Sind, the factional intrigues inside, the ministerial

posts, the total disintegration of party organisation and above all, the

shameless acceptance of and compromise with the reactionary ideology of its

defeated foes have created a most suitable climate for the anti-progressive

forces in Sind and Karachi to spread their tentacles. The opportunity has been

provided by the PPP leadership itself in the shape of the Language Bill. It was

an ideal example of doing the right thing at the wrong time!

Why did the PPP leadership push

through this controversial Bill with such indecent haste? What was the urgency

for its enactment at this critical juncture when the government was occupied

with other very serious national problems?

Various arguments have been advanced

in support of the Bill. For instance, it is said that the Sindhi language is as

old as Mohenjo-Daro (which is not correct historically, because the language of

Mohenjo-Dar people was Proto-Dravadian, while that of Sindhi people belongs to

the Indo-Aryan family) that it was neglected by the past rulers of Pakistan,

that it has been pushed aside to accommodate Urdu, that its age-old position

must be restored, that it is the birth-right of every Sindhi to communicate in

his mother tongue and develop it to the highest pinnacle.

The mother tongue of a very big

ethnological minority (almost 30%) happens to be Urdu and this community is as

deeply attached to Urdu as every old Sindhi is attached to Sindhi. Morever,

Urdu has been declared the national language of Pakistan and the provincial

language in the Punjab, NWFP and Baluchistan.

Herald archives

I fully agree with all these

arguments and can advance a few more in favour of the Sindhi language. But —

and it is an important but — the mother tongue of a very big ethnological

minority (almost 30%) happens to be Urdu and this community is as deeply attached

to Urdu as every old Sindhi is attached to Sindhi. Morever, Urdu has been

declared the national language of Pakistan and the provincial language in the

Punjab, NWFP and Baluchistan.

I am sure the authorities were fully

aware of the sentiments of the Urdu speaking people as well as the machinations

of the rightists, elements who were waiting for some excuse to discredit the

PPP Government in Sind. I cannot believe that our efficient Intelligence

Service which provided Mir Rasul Bux Talpur with evidence to prove that the

June agitation of the SITE workers’ was inspired b Russian and Indian agents

was caught unawares in July. Or was it that the administration underestimated

the mobilising capacity of the rightists elements on the basis of linguistic

sentiment? Or was it that the Language Bill was introduced at this inopportune

time to appease the chauvinistic section of the old Sindhi intelligentsia? Or

was it a deliberate attempt to distract the attention of the people from the

basic problems of life, which the PPP is finding hard to solve?

Whatever the motives or lack of

motives a government which claims to be socialist has played into the hands of

anti-socialist elements and given them a new lease of life.

These reactionaries could not

mobilize the masses against the People’s Party Government on the basis of any

political or economic programme. They failed to arouse even against the Simla

Agreement. They also failed to make capital out of the POW issue. But the issue

of language was different.

If any evidence was required to

prove that the language controversy is essentially a socio-economic phenomenon,

it was provided by the agitators themselves. While the early slogans were quite

innocuous “Urdu Sindhi Saath Saath”—the mood changed as the agitation gained

momentum. Soon the formality of tying Urdu with Sindhi was discarded and the

call was confined to “Urdu only”. Then even Urdu was forgotten and the demand

for a separate Province of Karachi was raised. This province was to be

“Mohajiristan.” The rate of the millions of Mohajirs living in the interior of

Sind never bothered these champions of Mohajiristan.

The Sindhi middle class wants

employment and opportunities to fully participate in the industrial, commercial

and business life of the province. So does the new Sindhi middle class.

Therefore, more and more avenues of employment have to be opened to absorb both

the groups. If the loaves are few and the number of hungry persons more,

quarrels are bound to occur.

Voices were also raised asking for

the dismissal of the Governor and Chief Minister of Sind and for additional

seats for the “representatives of Mohajirs” in the Cabinet. Suggestions were

also made that, like the Lebanon, where Christians and Muslims are evenly

balanced, certain key-posts in Sind should be reserved for Mohajirs. As if this

was not enough, slogans were written on the walls and roads eulogising the

“meritorious services of Ayub Khan.” And this happened of all places in Karachi

which had defeated the tyrant, in 1965 election in spite of his threats to

throw the Mohajirs into the Arabian Sea.

An accord has been reached between

the champions of Urdu and Sindhi. We sincerely hope that it satisfies the

legitimate aspirations of both and its implemented in letter and spirit. But

certain drastic measures will have to be taken to remove the socio economic

causes of discord. Fervent appeals are being made in the name of God, in the

name of Islam, in the name of Pakistani Nationhood, to the inhabitants of Sind

to live like brothers and behave like good neighbours. But these appeals will

fall on deaf ears if the roots of unrest and resentment are not permanently

removed.

The Sindhi middle class wants

employment and opportunities to fully participate in the industrial, commercial

and business life of the province. So does the new Sindhi middle class.

Therefore, more and more avenues of employment have to be opened to absorb both

the groups. If the loaves are few and the number of hungry persons more,

quarrels are bound to occur.

The haris want land. They must be

provided with enough land and other facilities so that they can improve their

standard of life and educate their children and liberate themselves from the

domination of waderas, pirs and other parasitical elements. Today these

elements incite the simple minded haris on parochial slogans to grab the lands

of the new Sindhi cultivators lest the haris demand the distribution of the

waderas’ land also.

The conflict between the haris and

the new Sindhi cultivators can be resolved when lands belonging to both the old

and new Sindhi landlords are taken over and equitably distributed among the

peasants — whether new or old. This will also cause a death blow to the feudal

system of Sind.

The administrative machinery should

be thoroughly overhauled and the power of bureaucracy drastically curtailed.

Administration at all levels should be entrusted as far as possible to the

democratically elected representatives of the people.

A Five-Year Plan for the development

of Sind, with special bias towards the interior, should be started immediately

and small Sindhis entrepreneurs be provided with capital, implements and

technical assistance to open industrial and commercial concern in the interior.

All private banks and large scale

industries, including foreign concerns should be properly and fully

nationalised.

The administrative machinery should

be thoroughly overhauled and the power of bureaucracy drastically curtailed.

Administration at all levels should be entrusted as far as possible to the

democratically elected representatives of the people.

Unless these and similar measures

are taken in right earnest conflicts between the two groups are bound to occur

on one pretext or the other. Today language is the bone of contention. Tomorrow

it may be admissions to colleges, or quota in services. We have got to stop

this civil war for good, otherwise the future of Pakistan is very bleak indeed!